What are the 3 techniques used to rank people according to class? Describe and explain.

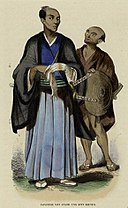

From top-left to bottom-correct or from pinnacle to bottom (mobile): a samurai and his retainer, c. 1846; The Slave Trader, painting by Géza Udvary, unknown appointment; a butler places a telephone call, 1922; The Bower Garden, painting by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 1859

A social class is a set of concepts in the social sciences and political theory centered on models of social stratification that occur in a class society, in which people are grouped into a ready of hierarchical social categories,[ane] the most common being the upper, middle and lower classes. Membership in a social class can for instance be dependent on education, wealth, occupation, income, and belonging to a particular subculture or social network.[2]

"Grade" is a subject of analysis for sociologists, political scientists, anthropologists and social historians. The term has a broad range of sometimes alien meanings, and in that location is no broad consensus on a definition of "class". Some people argue that due to social mobility, form boundaries do not exist. In common parlance, the term "social form" is usually synonymous with "socio-economic class", defined as "people having the same social, economic, cultural, political or educational status", eastward.g., "the working class"; "an emerging professional class".[three] However, academics distinguish social grade from socioeconomic status, using the former to refer to ane's relatively stable sociocultural background and the latter to refer to i'southward current social and economic situation which is consequently more than changeable over time.[4]

The precise measurements of what determines social course in society take varied over time. Karl Marx thought "class" was defined by one's relationship to the means of production (their relations of product). His understanding of classes in modern backer society is that the proletariat piece of work but do not ain the means of production, and the bourgeoisie, those who invest and live off the surplus generated by the proletariat's functioning of the means of product, do non work at all. This contrasts with the view of the sociologist Max Weber, who argued that "class" is determined by economic position, in dissimilarity to "social condition" or "Stand up" which is determined by social prestige rather than simply only relations of production.[5] The term "grade" is etymologically derived from the Latin classis, which was used by census takers to categorize citizens by wealth in order to determine military machine service obligations.[6]

In the late 18th century, the term "class" began to replace classifications such equally estates, rank and orders every bit the chief ways of organizing society into hierarchical divisions. This corresponded to a general subtract in significance ascribed to hereditary characteristics and increase in the significance of wealth and income as indicators of position in the social hierarchy.[7] [viii]

History [edit]

Ancient Egypt [edit]

The existence of a course organisation dates back to times of Ancient Egypt, where the position of elite was also characterized by literacy.[nine] The wealthier people were at the height in the social order and common people and slaves being at the bottom.[10] However, the class was not rigid; a man of apprehensive origins could ascend to a high post.[11] : 38-

The ancient Egyptians viewed men and women, including people from all social classes, as substantially equal nether the constabulary, and fifty-fifty the lowliest peasant was entitled to petition the vizier and his court for redress.[12]

Farmers made up the bulk of the population, simply agricultural produce was endemic direct by the land, temple, or noble family unit that owned the country.[13] : 383 Farmers were also subject to a labor tax and were required to piece of work on irrigation or construction projects in a corvée organisation.[14] : 136 Artists and craftsmen were of college condition than farmers, simply they were too under land control, working in the shops attached to the temples and paid straight from the country treasury. Scribes and officials formed the upper class in ancient Egypt, known every bit the "white kilt class" in reference to the bleached linen garments that served as a marking of their rank.[15] : 109 The upper class prominently displayed their social condition in art and literature. Below the nobility were the priests, physicians, and engineers with specialized training in their field. It is unclear whether slavery equally understood today existed in ancient Arab republic of egypt; there is difference of opinions amid authors.[16]

Slave chirapsia in ancient Egypt

Not a single Egyptian was, in our sense of the word, free. No private could phone call in question a hierarchy of authority which culminated in a living god.

Although slaves were more often than not used as indentured servants, they were able to buy and sell their servitude, work their way to liberty or nobility, and were usually treated by doctors in the workplace.[17]

Elsewhere [edit]

In Ancient Greece when the clan arrangement [a] was declining. The classes[b] replaced the clan society when it became besides small to sustain the needs of increasing population. The sectionalisation of labor is also essential for the growth of classes.[xi] : 39

Nigerian warriors armed with spears in the retinue of a mounted war principal. The Globe and Its Inhabitants, 1892

Historically, social class and behavior were laid down in law. For example, permitted manner of wearing apparel in some times and places was strictly regulated, with sumptuous dressing only for the high ranks of society and aristocracy, whereas sumptuary laws stipulated the clothes and jewelry appropriate for a person'south social rank and station. In Europe, these laws became increasingly commonplace during the Middle Ages. Still, these laws were prone to alter due to societal changes, and in many cases, these distinctions may either almost disappear, such as the distinction betwixt a patrician and a plebeian existence almost erased during the tardily Roman Commonwealth.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau had a large influence over political ethics of the French Revolution considering of his views of inequality and classes. Rousseau saw humans equally "naturally pure and skilful," meaning that humans from nascency were seen as innocent and any evilness was learned. He believed that social problems arise through the evolution of gild and suppress the innate pureness of humankind. He also believed that private property is the main reason for social issues in society considering individual holding creates inequality through the property'south value. Even though his theory predicted if there were no private property and then at that place would be wide spread equality, Rousseau accepted that there will always exist social inequality considering of how society is viewed and run.[xviii]

Later Enlightenment thinkers viewed inequality every bit valuable and crucial to society'south development and prosperity. They also best-selling that private property volition ultimately cause inequality considering specific resources that are privately owned can exist stored and the owners profit off of the deficit of the resource. This can create competition between the classes that was seen as necessary by these thinkers.[18] This also creates stratification betwixt the classes keeping a distinct difference between lower, poorer classes and the higher, wealthier classes.

India (↑), Nepal, North Korea (↑), Sri Lanka (↑) and some Indigenous peoples maintain social classes today.

In class societies, form conflict has tended to recur or is ongoing, depending on the sociological and anthropolitical perspective.[19] [20] Class societies have not always existed; there have been widely dissimilar types of class communities.[21] [22] [23] For case, societies based on historic period rather than capital letter.[24] During colonialism, social relations were dismantled by force, which gave rising to societies based on the social categories of waged labor, private property, and capital letter.[24] [25]

Class society [edit]

Class lodge or class-based society is an organizing principle social club in which ownership of property, means of production, and wealth is the determining factor of the distribution of ability, in which those with more property and wealth are stratified higher in the gild and those without access to the means of product and without wealth are stratified lower in the society. In a course society, at to the lowest degree implicitly, people are divided into singled-out social strata, commonly referred to as social classes or castes. The nature of class club is a affair of sociological inquiry.[26] [27] [28] Class societies exist all over the globe in both industrialized and developing nations.[29] Form stratification is theorized to come straight from capitalism.[30] In terms of public opinion, ix out of x people in a Swedish survey considered information technology right that they are living in a grade society.[31]

Comparative sociological research [edit]

One may use comparative methods to written report form societies, using, for example, comparison of Gini coefficients, de facto educational opportunities, unemployment, and culture.[32] [33]

Effect on the population [edit]

Societies with big class differences have a greater proportion of people who suffer from mental health bug such as feet and depression symptoms.[34] [35] [36] A series of scientific studies have demonstrated this relationship.[37] Statistics support this assertion and results are found in life expectancy and overall health; for instance, in the instance of high differences in life expectancy between 2 Stockholm suburbs. The differences between life expectancy of the poor and less-well-educated inhabitants who alive in proximity to the station Vårby gård, and the highly educated and more than affluent inhabitants living near Danderyd differ by xviii years.[38] [39]

Similar data most New York is also available for life expectancy, average income per capita, income distribution, median income mobility for people who grew upwards poor, share with a bachelor's degree or college.[40]

In class societies, the lower classes systematically receive lower-quality didactics and intendance.[41] [42] [43] In that location are more than explicit furnishings where those within the higher class actively demonize parts of the lower-class population.[33]

Theoretical models [edit]

Definitions of social classes reflect a number of sociological perspectives, informed past anthropology, economics, psychology and sociology. The major perspectives historically have been Marxism and structural functionalism. The common stratum model of grade divides social club into a simple hierarchy of working class, eye class and upper class. Inside academia, 2 broad schools of definitions emerge: those aligned with 20th-century sociological stratum models of form order and those aligned with the 19th-century historical materialist economic models of the Marxists and anarchists.[44] [45] [46]

Another distinction can be drawn between analytical concepts of social class, such every bit the Marxist and Weberian traditions, too as the more empirical traditions such as socioeconomic condition approach, which notes the correlation of income, education and wealth with social outcomes without necessarily implying a item theory of social structure.[47]

Marxist [edit]

"[Classes are] big groups of people differing from each other by the place they occupy in a historically determined arrangement of social production, past their relation (in most cases stock-still and formulated in law) to the means of production, past their role in the social organization of labor, and, consequently, by the dimensions of the share of social wealth of which they dispose and the mode of acquiring it."

—Vladimir Lenin, A Neat First on June 1919

For Marx, grade is a combination of objective and subjective factors. Objectively, a class shares a common relationship to the means of production. The grade society itself is understood as the aggregated phenomenon to the "interlinked movement", which generates the quasi-objective concept of capital letter.[48] Subjectively, the members volition necessarily take some perception ("class consciousness") of their similarity and common interest. Class consciousness is non merely an sensation of i'southward own class involvement but is too a set of shared views regarding how order should exist organized legally, culturally, socially and politically. These grade relations are reproduced through time.

In Marxist theory, the class structure of the capitalist style of production is characterized by the conflict between two main classes: the bourgeoisie, the capitalists who own the means of product and the much larger proletariat (or "working course") who must sell their own labour power (wage labour). This is the fundamental economical structure of piece of work and belongings, a country of inequality that is normalized and reproduced through cultural ideology.

For Marxists, every person in the procedure of production has carve up social relationships and bug. Forth with this, every person is placed into different groups that have similar interests and values that can differ drastically from group to group. Class is special in that does not relate to specifically to a atypical person, simply to a specific role.[eighteen]

Marxists explain the history of "civilized" societies in terms of a war of classes betwixt those who control product and those who produce the goods or services in society. In the Marxist view of capitalism, this is a conflict between capitalists (bourgeoisie) and wage-workers (the proletariat). For Marxists, class antagonism is rooted in the situation that control over social product necessarily entails control over the class which produces appurtenances—in capitalism this is the exploitation of workers by the bourgeoisie.[49]

Furthermore, "in countries where modern culture has become fully developed, a new class of petty bourgeois has been formed".[fifty] "An industrial regular army of workmen, under the command of a capitalist, requires, like a real army, officers (managers) and sergeants (foremen, over-lookers) who, while the work is existence washed, command in the name of the capitalist".[51]

Marx makes the argument that, every bit the suburbia reach a point of wealth accumulation, they hold enough ability as the dominant class to shape political institutions and society co-ordinate to their own interests. Marx then goes on to claim that the non-elite class, owing to their large numbers, take the power to overthrow the aristocracy and create an equal club.[52]

In The Communist Manifesto, Marx himself argued that information technology was the goal of the proletariat itself to displace the capitalist system with socialism, changing the social relationships underpinning the course system and and so developing into a future communist society in which: "the complimentary development of each is the status for the free development of all". This would mark the outset of a classless society in which homo needs rather than turn a profit would be motive for production. In a society with democratic control and production for use, there would be no class, no land and no need for financial and banking institutions and coin.[53] [54]

These theorists accept taken this binary class organisation and expanded it to include contradictory class locations, the idea that a person tin can exist employed in many different class locations that fall between the two classes of proletariat and suburbia. Erik Olin Wright stated that class definitions are more diverse and elaborate through identifying with multiple classes, having familial ties with people in different a class, or having a temporary leadership role.[18]

Weberian [edit]

Max Weber formulated a three-component theory of stratification that saw social class as emerging from an interplay betwixt "class", "condition" and "ability". Weber believed that class position was adamant by a person's relationship to the means of production, while condition or "Stand up" emerged from estimations of honor or prestige.[55]

Weber views class as a group of people who take mutual goals and opportunities that are available to them. This means that what separates each class from each other is their value in the marketplace through their own goods and services. This creates a split between the classes through the assets that they accept such equally property and expertise.[eighteen]

Weber derived many of his key concepts on social stratification by examining the social structure of many countries. He noted that opposite to Marx's theories, stratification was based on more simply ownership of capital. Weber pointed out that some members of the elite lack economic wealth yet might nonetheless have political power. As well in Europe, many wealthy Jewish families lacked prestige and accolade because they were considered members of a "pariah group".

- Class: A person's economic position in a society. Weber differs from Marx in that he does not see this as the supreme factor in stratification. Weber noted how managers of corporations or industries control firms they practice not ain.

- Condition: A person'south prestige, social award or popularity in a society. Weber noted that political power was non rooted in upper-case letter value solely, only besides in one'due south status. Poets and saints, for example, tin can possess immense influence on club with often little economic worth.

- Power: A person'due south power to become their way despite the resistance of others. For example, individuals in state jobs, such as an employee of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, or a member of the United states Congress, may hold petty property or status, merely they still concur immense power.

Bourdieu [edit]

For Bourdieu, the place in the social strata for any person is vaguer than the equivalent in Weberian folklore. Bourdieu introduced an assortment of concepts of what he refers to as types of uppercase. These types were economical capital letter, in the form avails convertible to money and secured as private property. This type of capital letter is separated from the other types of culturally constituted types of uppercase, which Bourdieu introduces, which are: personal cultural capital (formal pedagogy, noesis); objective cultural capital (books, fine art); and institutionalized cultural capital (honours and titles).

Swell British Course Survey [edit]

On 2 April 2013, the results of a survey[56] conducted past BBC Lab United kingdom developed in collaboration with academic experts and slated to be published in the journal Sociology were published online.[57] [58] [59] [60] [61] The results released were based on a survey of 160,000 residents of the United Kingdom most of whom lived in England and described themselves every bit "white". Grade was defined and measured according to the corporeality and kind of economic, cultural and social resources reported. Economic capital was defined as income and avails; cultural capital as amount and type of cultural interests and activities; and social capital equally the quantity and social status of their friends, family and personal and business contacts.[60] This theoretical framework was adult by Pierre Bourdieu who first published his theory of social distinction in 1979.

3-level economic form model [edit]

Today, concepts of social form often presume three general economical categories: a very wealthy and powerful upper course that owns and controls the means of product; a middle class of professional workers, pocket-sized business owners and low-level managers; and a lower class, who rely on low-paying jobs for their livelihood and experience poverty.

Upper course [edit]

A symbolic image of three orders of feudal club in Europe prior to the French Revolution, which shows the rural third estate conveying the clergy and the nobility

The upper class[62] is the social class composed of those who are rich, well-born, powerful, or a combination of those. They ordinarily wield the greatest political ability. In some countries, wealth lonely is sufficient to allow entry into the upper class. In others, only people who are born or marry into certain aristocratic bloodlines are considered members of the upper class and those who gain great wealth through commercial activity are looked downwards upon past the aristocracy as nouveau riche.[63] In the United Kingdom, for example, the upper classes are the aristocracy and royalty, with wealth playing a less important role in class status. Many aristocratic peerages or titles take seats fastened to them, with the holder of the title (e.g. Earl of Bristol) and his family unit being the custodians of the house, but non the owners. Many of these require loftier expenditures, so wealth is typically needed. Many aristocratic peerages and their homes are parts of estates, owned and run by the title holder with moneys generated by the land, rents or other sources of wealth. However, in the U.s. where there is no aristocracy or royalty, the upper class status belongs to the extremely wealthy, the and so-chosen "super-rich", though there is some tendency even in the United States for those with one-time family wealth to wait downwardly on those who have earned their money in business, the struggle between new money and old coin.

The upper form is generally contained inside the richest i or 2 pct of the population. Members of the upper class are frequently born into it and are distinguished past immense wealth which is passed from generation to generation in the course of estates.[64] Based on some new social and political theories upper grade consists of the most wealthy decile group in guild which holds most 87% of the whole society'southward wealth.[65]

Middle class [edit]

Come across also: Eye-course squeeze

The middle grade is the most contested of the three categories, the broad grouping of people in contemporary society who fall socio-economically between the lower and upper classes.[66] I case of the contest of this term is that in the United States "middle class" is applied very broadly and includes people who would elsewhere be considered working class. Middle-class workers are sometimes called "white-collar workers".

Theorists such as Ralf Dahrendorf have noted the tendency toward an enlarged eye course in mod Western societies, especially in relation to the necessity of an educated work force in technological economies.[67] Perspectives concerning globalization and neocolonialism, such as dependency theory, suggest this is due to the shift of low-level labour to developing nations and the Third World.[68]

Middle form is the group of people with typical-everyday jobs that pay significantly more than than the poverty line. Examples of these types of jobs are factory workers, salesperson, teacher, cooks and nurses. There is a new trend past some scholars which assumes that the size of the middle class in every society is the same. For example, in paradox of interest theory, center grade are those who are in 6th–ninth decile groups which hold about 12% of the whole club'south wealth.[69]

Lower form [edit]

In the United states of america the lowest stratum of the working class, the underclass, often lives in urban areas with low-quality ceremonious services

Lower course (occasionally described every bit working grade) are those employed in low-paying wage jobs with very piffling economic security. The term "lower class" also refers to persons with low income.

The working class is sometimes separated into those who are employed but defective financial security (the "working poor") and an underclass—those who are long-term unemployed and/or homeless, peculiarly those receiving welfare from the country. The latter is today considered analogous to the Marxist term "lumpenproletariat". However, during the fourth dimension of Marx'south writing the lumpenproletariat referred to those in dire poverty; such as the homeless.[62] Members of the working grade are sometimes called bluish-collar workers.

Consequences of grade position [edit]

A person's socioeconomic class has broad-ranging effects. It tin can affect the schools they are able to attend,[70] [71] [72] [73] [74] [75] their health,[76] the jobs open to them,[70] when they get out the labour market,[77] whom they may ally[78] and their treatment by police and the courts.[79]

Angus Deaton and Anne Example accept analyzed the mortality rates related to the group of white, middle-anile Americans between the ages of 45 and 54 and its relation to form. There has been a growing number of suicides and deaths by substance abuse in this particular group of eye-grade Americans. This group too has been recorded to have an increase in reports of chronic hurting and poor general health. Deaton and Instance came to the conclusion from these observations that considering of the constant stress that these white, eye aged Americans experience fighting poverty and wavering between the middle and lower classes, these strains accept taken a toll on these people and affected their whole bodies.[76]

Social classifications tin also determine the sporting activities that such classes take part in. It is suggested that those of an upper social class are more than likely to take part in sporting activities, whereas those of a lower social background are less likely to participate in sport. However, upper-class people tend to not take part in certain sports that have been commonly known to be linked with the lower course.[80]

[edit]

Education [edit]

A person's social grade has a significant impact on their educational opportunities. Not merely are upper-class parents able to send their children to exclusive schools that are perceived to exist better, only in many places, country-supported schools for children of the upper course are of a much higher quality than those the country provides for children of the lower classes.[81] [82] [83] [84] [85] [86] This lack of good schools is i factor that perpetuates the class divide across generations.

In the Great britain, the educational consequences of class position have been discussed by scholars inspired by the cultural studies framework of the CCCS and/or, peculiarly regarding working-course girls, feminist theory. On working-course boys, Paul Willis' 1977 volume Learning to Labour: How Working Class Kids Get Working Class Jobs is seen within the British Cultural Studies field as a classic give-and-take of their antipathy to the acquisition of knowledge.[87] Beverley Skeggs described Learning to Labour every bit a study on the "irony" of "how the process of cultural and economic reproduction is fabricated possible by 'the lads' ' commemoration of the hard, macho world of work."[88]

Health and diet [edit]

A person'south social form has a significant impact on their physical health, their power to receive adequate medical intendance and nutrition and their life expectancy.[89] [90] [91]

Lower-class people experience a wide assortment of health issues as a result of their economic condition. They are unable to apply health care as often and when they do it is of lower quality, even though they generally tend to experience a much higher rate of health issues. Lower-course families have higher rates of infant mortality, cancer, cardiovascular disease and disabling physical injuries. Additionally, poor people tend to work in much more chancy conditions, yet generally take much less (if any) health insurance provided for them, every bit compared to middle- and upper-course workers.[92]

Employment [edit]

The weather condition at a person'southward chore vary greatly depending on class. Those in the upper-middle class and centre class savour greater freedoms in their occupations. They are usually more than respected, savor more diversity and are able to exhibit some authority.[93] Those in lower classes tend to experience more than alienated and take lower work satisfaction overall. The physical conditions of the workplace differ profoundly betwixt classes. While eye-grade workers may "suffer alienating conditions" or "lack of task satisfaction", blue-collar workers are more than apt to suffer alienating, often routine, work with obvious concrete health hazards, injury and even death.[94]

In the UK, a 2015 government written report by the Social Mobility Commission suggested the existence of a "glass floor" in British guild preventing those who are less able, but who come up from wealthier backgrounds, from slipping downwards the social ladder. The report proposed a 35% greater likelihood of less able, better-off children becoming high earners than bright poor children.[95]

Course disharmonize [edit]

Class conflict, frequently referred to as "class warfare" or "form struggle", is the tension or antagonism which exists in society due to competing socioeconomic interests and desires between people of different classes.

For Marx, the history of class order was a history of class conflict. He pointed to the successful ascent of the bourgeoisie and the necessity of revolutionary violence—a heightened form of grade conflict—in securing the bourgeois rights that supported the capitalist economy.

Marx believed that the exploitation and poverty inherent in capitalism were a pre-existing form of class conflict. Marx believed that wage labourers would need to revolt to bring nearly a more equitable distribution of wealth and political ability.[96] [97]

Classless gild [edit]

A "classless" society is 1 in which no 1 is built-in into a social course. Distinctions of wealth, income, teaching, culture or social network might arise and would simply be adamant by individual experience and achievement in such a society.

Since these distinctions are difficult to avoid, advocates of a classless society (such as anarchists and communists) advise various means to achieve and maintain information technology and attach varying degrees of importance to it as an cease in their overall programs/philosophy.

Relationship between ethnicity and form [edit]

Race and other large-scale groupings tin can also influence class continuing. The association of particular indigenous groups with class statuses is common in many societies, and is linked with race as well.[98] Class and ethnicity can touch on a persons, or communities, Socioeconomic standing, which in turn influences everything including job availability and the quality of bachelor health and education.[99] The labels ascribed to an individual change the way others perceive them, with multiple labels associated with stigma combining to worsen the social consequences of being labelled.[100]

As a consequence of conquest or internal indigenous differentiation, a ruling form is oft ethnically homogenous and particular races or indigenous groups in some societies are legally or customarily restricted to occupying particular class positions. Which ethnicities are considered as belonging to high or depression classes varies from club to social club.

In modern societies, strict legal links between ethnicity and grade have been drawn, such equally the caste system in Africa, apartheid, the position of the Burakumin in Japanese society and the casta organisation in Latin America.[ citation needed ]

See also [edit]

- Class stratification

- Degree

- Migrate hypothesis

- Elite theory

- Elitism

- Four occupations

- Wellness disinterestedness

- Hostile architecture

- Inca society

- Korean ruling class

- Mass order

- National Statistics Socio-economic Classification

- Passing (sociology)

- Post-industrial order

- Ranked guild

- Raznochintsy

- Psychology of social form

- Social stratification

- Welfare state

Notes [edit]

- ^ based on blood relations

- ^ based on occupation

References [edit]

- ^ Grant, J. Andrew (2001). "form, definition of". In Jones, R.J. Barry (ed.). Routledge Encyclopedia of International Political Economy: Entries A–F. Taylor & Francis. p. 161. ISBN978-0-415-24350-6.

- ^ "The Course Construction in the U.Due south. | Boundless Sociology". courses.lumenlearning.com . Retrieved 5 March 2021.

- ^ Princeton University. "Social class". WordNet Search iii.1. Retrieved on: 2012-01-25.

- ^ Rubin, M., Denson, N., Kilpatrick, Southward., Matthews, K.E., Stehlik, T., & Zyngier, D. (2014). ""I am working-course": Subjective cocky-definition equally a missing measure of social course and socioeconomic status in college education research". Educational Researcher. 43 (4): 196–200. doi:10.3102/0013189X14528373. hdl:1959.13/1043609. S2CID 145576929.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ^ Weber, Max (1921/2015). "Classes, Stände, Parties" in Weber'due south Rationalism and Modern Lodge: New Translations on Politics, Bureaucracy and Social Stratification. Edited and Translated by Tony Waters and Dagmar Waters, pp. 37–58.

- ^ Brownish, D.F. (2009). "Social class and Status". In Mey, Jacob (ed.). Concise Encyclopedia of Pragmatics. Elsevier. p. 952. ISBN978-0-08-096297-nine.

- ^ Kuper, Adam, ed. (2004). "Class, Social". The social science encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. p. 111. ISBN978-0-415-32096-ii.

- ^ Penney, Robert (2003). "Class, social". In Christensen, Karen; Levinson, David (eds.). Encyclopedia of community: from the village to the virtual world, Volume 1. SAGE. p. 189. ISBN978-0-7619-2598-9.

- ^ Barbara Mendoza (5 October 2017). Artifacts from Ancient Egypt. ABC-CLIO. pp. 216–. ISBN978-i-4408-4401-0.

- ^ Tracey Baptiste (xv December 2015). The Totally Gross History of Ancient Egypt. The Rosen Publishing Grouping, Inc. pp. v–. ISBN978-1-4994-3755-3.

- ^ a b c Keller, Suzanne (2017). Across the Ruling Course: Strategic Elites in Modern Society. Routledge. ISBN9781351289184.

- ^ Johnson, Janet H. (2002). "Women'due south Legal Rights in Ancient Egypt". Fathom Annal. University of Chicago.

- ^ Manuelian, Peter Der (1998). Regine Schulz; Matthias Seidel (eds.). Egypt: The World of the Pharaohs. Cologne, Deutschland: Könemann. ISBN978-iii-89508-913-8.

- ^ James, T.G.H. (2005). The British Museum Curtailed Introduction to Ancient Egypt. University of Michigan Press. ISBN978-0-472-03137-5.

- ^ Billard, Jules B. (1978). Aboriginal Egypt, Discovering Its Splendors. National Geographic Society. ISBN9780870442209.

- ^ "Social classes in ancient Egypt". Digital Egypt for Universities. University Higher London. 2003. Archived from the original on 13 December 2007.

- ^ "Slavery". An introduction to the history and culture of Pharaonic Arab republic of egypt. Archived from the original on 30 August 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Conley, Dalton (2017). "Stratification". In Bakeman, Karl (ed.). Yous May Enquire Yourself: An Introduction to Thinking like a Sociologist (5th ed.). Due west.W. Norton & Company, Inc. ISBN978-0393614275.

- ^ The concise encyclopedia of sociology. Wiley-Blackwell. 2011. p. 66. ISBN978-1-4443-9263-0. OCLC 701327736.

- ^ Weapons of the weak : everyday forms of peasant resistance. ISBN978-0-585-36330-1. OCLC 317459153.

- ^ EVOLUTION OF PROPERTY FROM SAVAGERY TO Culture. HANSEBOOKS. 2017. ISBN978-3-337-31218-3. OCLC 1104923720.

- ^ Aboriginal society. Transaction Publishers. 2000. ISBN0-7658-0691-6. OCLC 44516641.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Western colonialism since 1450. Macmillan Reference United states of america. 2007. pp. 620, 849, 921, 64. ISBN978-0-02-866085-1. OCLC 74840473.

- ^ a b Historic period course systems : social institutions and polities based on age. Cambridge Academy Printing. 1985. ISBN0-521-30747-three. OCLC 11621536.

- ^ https://www.constabulary.uci.edu/lawreview/vol4/no1/Bhandar.pdf[ blank URL PDF ]

- ^ Drobnic, S.; Guillén, A. (2011). Work-Life Remainder in Europe: The Part of Job Quality. Springer. p. 208. ISBN9780230307582.

- ^ "Essays on Social Reproduction and Lifelong Learning". Skolporten. 14 April 2010. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- ^ Bihagen, Erik; Nermo, Magnus; Stern, Charlotta (Oct 2013). "Class Origin and Elite Position of Men in Business concern Firms in Sweden, 1993–2007: The Importance of Education, Cerebral Ability, and Personality". European Sociological Review. 29 (five): 939–954. doi:10.1093/esr/jcs070.

- ^ "Global Stratification and Inequality | Introduction to Sociology". courses.lumenlearning.com . Retrieved i June 2020.

- ^ Lane, David (1 December 2005). "Social course as a factor in the transformation of state socialism". Periodical of Communist Studies and Transition Politics. 21 (4): 417–435. doi:x.1080/13523270500363361. ISSN 1352-3279. S2CID 154779478.

- ^ "Klassamhället åter anser nine av 10" (in Swedish). 26 April 2004. ISSN 1101-2412.

- ^ https://world wide web.ifs.org.uk/docs/ER_JC_2013.pdf[ bare URL PDF ]

- ^ a b Jones, Owen Peter (2011). Chavs : the demonization of the working grade : with new preface ([New] ed.). ISBN978-ane-78168-398-9. OCLC 1105199910.

- ^ Wilkinson, Richard Yard; Pickett, Kate (2019). The inner level : how more than equal societies reduce stress, restore sanity and improve everyone'southward well-existence. Penguin Books. ISBN978-0-14-197539-ix. OCLC 1091644373.

- ^ Salmi, Peter (13 Dec 2017). "Kraftig ökning av psykisk ohälsa bland barn och unga vuxna". Socialstyrelsen (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 21 February 2018.

- ^ Mathisen, Daniel (8 June 2018). "Inte konstigt att klassamhället får oss att må dåligt" (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 20 June 2019. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- ^ Aneshensel, Carol S; Phelan, Jo C (1999). Handbook of the sociology of mental health. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. p. 152. ISBN978-0-387-36223-six. OCLC 552063104.

- ^ "Var du bor avgör när du dör" (in Swedish). 12 May 2014.

- ^ "Mera om massiva och dödliga klasskillnader" (in Swedish). 29 June 2019. ISSN 1101-2412.

- ^ Leonhardt, David; Serkez, Yaryna (13 May 2020). "Opinion | What Does Opportunity Look Like Where You Alive?". The New York Times.

- ^ "Skillnad mellan rika och fattigas överlevnad i bröstcancer".

- ^ Closing the gap in a generation : health equity through action on the social determinants of wellness : Commission on Social Determinants of Wellness final written report. World Health Organization, Committee on Social Determinants of Wellness. 2008. ISBN978-92-4-156370-3. OCLC 248038286.

- ^ "Fattiga klarar cancer sämst" (in Swedish). eight September 2008. ISSN 1101-2412.

- ^ Serravallo, Vincent (2008). "Form". In Parrillo, Vincent N. (ed.). Encyclopedia of social problems, Volume 1. SAGE. p. 131. ISBN978-1-4129-4165-5.

- ^ Gilbert, Dennis (1998). The American Class Construction . New York: Wadsworth Publishing. ISBN978-0-534-50520-2.

- ^ Williams, Brian; Stacey C. Sawyer; Carl M. Wahlstrom (2005). Marriages, Families & Intimate Relationships. Boston: Pearson. ISBN978-0-205-36674-3.

- ^ John Scott, Grade: critical concepts (1996) Volume ii P. 310

- ^ https://libcom.org/file [ permanent dead link ] /Moishe%20Postone%twenty-%20Time,%20Labor,%20and%20Social%20Domination.pdf

- ^ Karl Marx & Friedrich Engels. "Manifesto of the Communist Party", Selected Works, Volume one; London,' 1943; p. 231.

- ^ Karl Marx & Friedrich Engels. "Manifesto of the Communist Party", Selected Works, Book ane; London,' 1943; p. 231

- ^ Karl Marx. Capital: An Analysis of Capitalist Product, Volume 1; Moscow; 1959; p. 332.

- ^ "Manifesto of the Communist Party". www.marxists.org . Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- ^ Karl Marx & Friedrich Engels. "Manifesto of the Communist Political party", Selected Works, Book 1; London,' 1943; p. 232-234.

- ^ Karl Marx Critique of the Gotha Program (1875)

- ^ Weber, Max (2015/1921). "Classes, Stände, Parties" in Weber's Rationalism and Modern Club, edited and translated by Tony Waters and Dagmar Waters, pp. 37–57.

- ^ "Britain's Existent Class Organization: Great British Class Survey". BBC Lab UK. Retrieved 4 April 2013. [ permanent expressionless link ]

- ^ Savage, Mike; Devine, Fiona; Cunningham, Niall; Taylor, Marker; Li, Yaojun; Johs. Hjellbrekke; Brigitte Le Roux; Friedman, Sam; Miles, Andrew (2 April 2013). "A New Model of Social Class: Findings from the BBC's Great British Class Survey Experiment" (PDF). Sociology. 47 (2): 219–50. doi:10.1177/0038038513481128. S2CID 85546872.

- ^ "The Corking British class figurer: People in the Britain now fit into seven social classes, a major survey conducted past the BBC suggests". BBC. three April 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ^ Savage, Mike; Devine, Fiona (3 Apr 2013). "The Neat British class calculator: Sociologists are interested in the idea that grade is about your cultural tastes and activities as well as the type and number of people you know". BBC . Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ^ a b Vicious, Mike; Devine, Fiona (3 April 2013). "The Great British class estimator: Mike Savage from the London School of Economics and Fiona Devine from the Academy of Manchester draw their findings from The Great British Form Survey. Their results identify a new model of class with vii classes ranging from the Elite at the superlative to a 'Precariat' at the bottom". BBC . Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ^ Lyall, Sarah (3 Apr 2013). "Multiplying the Quondam Divisions of Class in Britain". The New York Times . Retrieved 4 Apr 2013.

- ^ a b Dark-brown, D.F. (2009). "Social class and Status". In Mey, Jacob (ed.). Concise Encyclopedia of Pragmatics. Elsevier. p. 953. ISBN978-0-08-096297-nine.

- ^ The Random House Dictionary of the English language Language, "nouveau riche French Unremarkably Disparaging. a person who is newly rich", 1969, Random House

- ^ Akhbar-Williams, Tahira (2010). "Class Structure". In Smith, Jessie C. (ed.). Encyclopedia of African American Popular Culture, Volume i. ABC-CLIO. p. 322. ISBN978-0-313-35796-1.

- ^ Baizidi, Rahim (2 September 2019). "Paradoxical class: paradox of involvement and political conservatism in middle class". Asian Journal of Political Science. 27 (3): 272–285. doi:10.1080/02185377.2019.1642772. ISSN 0218-5377. S2CID 199308683.

- ^ Stearns, Peter Northward., ed. (1994). "Center class". Encyclopedia of social history. Taylor & Francis. p. 621. ISBN978-0-8153-0342-viii.

- ^ Dahrendorf, Ralf. (1959) Course and Class Conflict in Industrial Society. Stanford: Stanford University Printing.

- ^ Bornschier V. (1996), 'Western social club in transition' New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Publishers.

- ^ Baizidi, Rahim (17 July 2019). "Paradoxical class: paradox of interest and political conservatism in center class". Asian Journal of Political Science. 27 (three): 272–285. doi:10.1080/02185377.2019.1642772. ISSN 0218-5377. S2CID 199308683.

- ^ a b Escarce, José J (October 2003). "Socioeconomic Condition and the Fates of Adolescents". Health Services Research. 38 (5): 1229–34. doi:x.1111/1475-6773.00173. ISSN 0017-9124. PMC1360943. PMID 14596387.

- ^ Wilbur, Tabitha G.; Roscigno, Vincent J. (31 August 2016). "First-generation Disadvantage and College Enrollment/Completion". Socius. 2: 2378023116664351. doi:10.1177/2378023116664351. ISSN 2378-0231.

- ^ DiMaggio, Paul (1982). "Cultural Capital and School Success: The Touch on of Status Civilisation Participation on the Grades of U.S. Loftier School Students". American Sociological Review. 47 (2): 189–201. doi:10.2307/2094962. JSTOR 2094962.

- ^ Buchmann, Claudia; DiPrete, Thomas A. (23 June 2016). "The Growing Female Reward in Higher Completion: The Function of Family Background and Academic Accomplishment". American Sociological Review. 71 (4): 515–41. CiteSeerX10.one.1.487.8265. doi:10.1177/000312240607100401. S2CID 53390724.

- ^ Grodsky, Eric; Riegle-Crumb, Catherine (1 January 2010). "Those Who Cull and Those Who Don't: Social Groundwork and College Orientation". The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 627 (1): 14–35. doi:10.1177/0002716209348732. ISSN 0002-7162. S2CID 145193811.

- ^ Hurst, Allison L. (2009). "The Path to College: Stories of Students from the Working Class". Race, Gender & Course. xvi (1/2): 257–81. JSTOR 41658872.

- ^ a b Kolata, Gina (2 November 2015). "Death Rates Rising for Middle-Anile White Americans, Report Finds". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- ^ Murray, Emily T.; Carr, Ewan; Zaninotto, Paola; Head, Jenny; Xue, Baowen; Stansfeld, Stephen; Beach, Brian; Shelton, Nicola (nine October 2019). "Inequalities in time from stopping paid work to death: findings from the ONS Longitudinal Study, 2001–2011". J Epidemiol Community Health. 73 (12): 1101–1107. doi:10.1136/jech-2019-212487. ISSN 0143-005X. PMID 31611238. S2CID 204703259.

- ^ Laureau, A. (2011). Unequal childhoods: Form, race, and family life. Univ of California Press.

- ^ Harris, Alexes (2016). "Monetary Sanctions as Penalty for the Poor". A Pound of Flesh: Monetary Sanctions equally Penalty for the Poor. Russell Sage Foundation. ISBN978-0-87154-461-ii. JSTOR x.7758/9781610448550.

- ^ Wilson, Thomas C. (2002). "The Paradox of Social Class and Sports Involvement". International Review for the Folklore of Sport. 37: 5–16. doi:10.1177/1012690202037001001. S2CID 144129391.

- ^ Jonathan Kozol, Savage Inequalities, Crown, 1991

- ^ McDonough, Patricia Yard. (1997). Choosing colleges: how social grade and schools construction opportunity. SUNY Press. pp. 1–2. ISBN978-0-7914-3477-2.

- ^ Shin, Kwang-Yeong & Lee, Byoung-Hoon (2010). "Social grade and educational opportunity in Due south Korea". In Attewell, Paul; Newman, Katherine Southward. (eds.). Growing gaps: educational inequality around the earth. Oxford Academy Press. p. 105. ISBN978-0-19-973218-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ^ McNamee, Stephen J. & Miller, Robert Grand. (2009). The meritocracy myth . Rowman & Littlefield. p. 199. ISBN978-0-7425-6168-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ^ Thomas, Scott Fifty. & Bell, Angela (2007). "Social class and higher pedagogy: a reorganization of opportunities". In Weis, Lois (ed.). The Fashion Class Works: Readings on Schoolhouse, Family, and the Economic system. Taylor & Francis. p. 273. ISBN978-0-415-95707-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ^ Sacks, Peter (2007). Tearing down the gates confronting the course divide in American pedagogy. Academy of California Press. pp. 112–14. ISBN978-0-520-24588-four.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ^ Willis, Paul (1977). Learning to Labour: How Working Class Kids Get Working Class Jobs. Farnborough: Saxon Firm. ISBN 978-0-5660-0150-5

- ^ Skeggs, Beverley (1992). "Paul Willis, Learning to Labour". In Barker, Martin & Beezer, Anne (eds.). Reading into Cultural Studies. London: Routledge, p.181. ISBN 978-0-4150-6377-7

- ^ Barr, Donald A. (2008). Wellness disparities in the United States: social class, race, ethnicity, and wellness. JHU Press. pp. i–two. ISBN978-0-8018-8821-ii.

- ^ Gulliford, Martin (2003). "Equity and access to health care". In Gulliford, Martin; Morgan, Myfanwy (eds.). Access to wellness intendance. Psychology Press. p. 39. ISBN978-0-415-27546-0.

- ^ Budrys, Grace (2009). Unequal Health: How Inequality Contributes to Health Or Illness. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 183–84. ISBN978-0-7425-6507-iv.

- ^ Liu, William Ming (2010). Social Class and Classism in the Helping Professions: Research, Theory, and Exercise. SAGE. p. 29. ISBN978-ane-4129-7251-2.

- ^ Maclean, Mairi; Harvey, Charles; Kling, Gerhard (i June 2014). "Pathways to Power: Class, Hyper-Agency and the French Corporate Aristocracy" (PDF). Organization Studies. 35 (6): 825–55. doi:10.1177/0170840613509919. ISSN 0170-8406. S2CID 145716192.

- ^ Kerbo, Herald (1996). Social Stratification and Inequality. New York: The McGraw-Hill Companies Inc. pp. 231–33. ISBN978-0-07-034258-3.

- ^ Social Mobility and Child Poverty Commission. "New research exposes the 'glass flooring' in British order". www.gov.great britain . Retrieved 22 September 2015.

- ^ Streeter, Calvin L. (2008). "Community". In Mizrahi, Terry (ed.). Encyclopedia of social work, Volume 1. Oxford University Printing. p. 352. ISBN978-0-19-530661-3.

- ^ Hunt, Stephen (2011). "class conflict". In Ritzer, George; Ryan, J. Michael (eds.). The Concise Encyclopedia of Sociology. John Wiley & Sons. p. 66. ISBN978-1-4051-8353-6.

- ^ "Ethnic and Racial Minorities & Socioeconomic Status". world wide web.apa.org . Retrieved five March 2021.

- ^ https://www.apa.org/pi/ses/resource/publications/minorities[ blank URL ]

- ^ Jones, Pip; Bradbury, Liz (2018). Introducing Social Theory (Third ed.). Cambridge, U.k.: Polity Press. pp. 104–114. ISBN978-1-5095-0504-3.

Bibliography [edit]

- Ojämlikhetens dimensioner – Marie Evertsson & Charlotta Magnusson (red.) (In Swedish) ISBN 9789147111299

- Om konsten att lyfta sig själv i håret och behålla barnet i badvattnet : kritiska synpunkter på samhällsvetenskapens vetenskapsteori – Israel, Joachim (In Swedish) ISBN 91-29-43746-6

- The inner level : how more equal societies reduce stress, restore sanity and meliorate everyone'south well-beingness – Richard G Wilkinson; Kate Pickett ISBN 9780141975399

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 April 2019. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

{{cite spider web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

Further reading [edit]

- Archer, Louise et al. Higher Instruction and Social Course: Bug of Exclusion and Inclusion (RoutledgeFalmer, 2003) (ISBN 0-415-27644-6)

- Aronowitz, Stanley, How Class Works: Power and Social Movement, Yale Academy Press, 2003. ISBN 0-300-10504-5

- Barbrook, Richard (2006). The Class of the New (paperback ed.). London: OpenMute. ISBN978-0-9550664-7-4. Archived from the original on 1 August 2018. Retrieved xv March 2022.

- Beckert, Sven, and Julia B. Rosenbaum, eds. The American Bourgeoisie: Distinction and Identity in the Nineteenth Century (Palgrave Macmillan; 2011) 284 pages; Scholarly studies on the habits, manners, networks, institutions, and public roles of the American middle form with a focus on cities in the North.

- Benschop, Albert. Classes – Transformational Class Assay (Amsterdam: Spinhuis; 1993/2012).

- Bertaux, Daniel & Thomson, Paul; Pathways to Social Class: A Qualitative Approach to Social Mobility (Clarendon Press, 1997)

- Bisson, Thomas N.; Cultures of Power: Lordship, Status, and Procedure in Twelfth-Century Europe (Academy of Pennsylvania Printing, 1995)

- Blackledge, Paul (2011). "Why workers can alter the world". Socialist Review. Vol. 364. London. Archived from the original on 10 December 2011.

- Blau, Peter & Duncan Otis D.; The American Occupational Structure (1967) archetype study of structure and mobility

- Brady, David "Rethinking the Sociological Measurement of Poverty" Social Forces Vol. 81 No.3, (March 2003), pp. 715–51 (abstract online in Project Muse).

- Broom, Leonard & Jones, F. Lancaster; Opportunity and Attainment in Australia (1977)

- Cohen, Lizabeth; Consumer'southward Democracy, (Knopf, 2003) (ISBN 0-375-40750-2). (Historical analysis of the working out of form in the United States).

- Connell, R.W and Irving, T.H., 1992. Class Structure in Australian History: Poverty and Progress. Longman Cheshire.

- de Ste. Croix, Geoffrey (July–August 1984). "Class in Marx'due south conception of history, aboriginal and modern". New Left Review. I (146): 94–111. (Good study of Marx'south concept.)

- Dargin, Justin The Birth of Russia's Energy Class, Asia Times (2007) (skilful study of contemporary class formation in Russia, post communism)

- Day, Gary; Class, (Routledge, 2001) (ISBN 0-415-18222-0)

- Domhoff, Chiliad. William, Who Rules America? Power, Politics, and Social Change, Englewood Cliffs, NJ : Prentice-Hall, 1967. (Prof. Domhoff's companion site to the book at the Academy of California, Santa Cruz)

- Eichar, Douglas M.; Occupation and Class Consciousness in America (Greenwood Press, 1989)

- Fantasia, Rick; Levine, Rhonda F.; McNall, Scott M., eds.; Bringing Class Back in Gimmicky and Historical Perspectives (Westview Press, 1991)

- Featherman, David L. & Hauser Robert Thou.; Opportunity and Change (1978).

- Fotopoulos, Takis, Class Divisions Today: The Inclusive Democracy arroyo, Democracy & Nature, Vol. half dozen, No. ii, (July 2000)

- Fussell, Paul; Class (a painfully authentic guide through the American condition arrangement), (1983) (ISBN 0-345-31816-1)

- Giddens, Anthony; The Class Structure of the Advanced Societies, (London: Hutchinson, 1981).

- Giddens, Anthony & Mackenzie, Gavin (Eds.), Social Class and the Division of Labour. Essays in Honour of Ilya Neustadt (Cambridge: Cambridge Academy Press, 1982).

- Goldthorpe, John H. & Erikson Robert; The Constant Flux: A Report of Class Mobility in Industrial Society (1992)

- Grusky, David B. ed.; Social Stratification: Course, Race, and Gender in Sociological Perspective (2001) scholarly articles

- Hazelrigg, Lawrence East. & Lopreato, Joseph; Class, Conflict, and Mobility: Theories and Studies of Grade Structure (1972).

- Hymowitz, Kay; Marriage and Caste in America: Split up and Unequal Families in a Post-Marital Historic period (2006) ISBN 1-56663-709-0

- Kaeble, Helmut; Social Mobility in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries: Europe and America in Comparative Perspective (1985)

- Jakopovich, Daniel, The Concept of Grade, Cambridge Studies in Social Research, No. 14, Social Scientific discipline Research Group, University of Cambridge, 2014

- Jens Hoff, "The Concept of Course and Public Employees". Acta Sociologica, vol. 28, no. 3, July 1985, pp. 207–26.

- Mahalingam, Ramaswami; "Essentialism, Culture, and Power: Representations of Social Class" Journal of Social Issues, Vol. 59, (2003), pp. 733+ on India

- Mahony, Pat & Zmroczek, Christine; Class Matters: 'Working-Class' Women'south Perspectives on Social Class (Taylor & Francis, 1997)

- Manza, Jeff & Brooks, Clem; Social Cleavages and Political Change: Voter Alignments and U.South. Party Coalitions (Oxford University Press, 1999).

- Manza, Jeff; "Political Sociological Models of the U.S. New Bargain" Annual Review of Sociology, (2000) pp. 297+

- Manza, Jeff; Hout, Michael; Clem, Brooks (1995). "Class Voting in Capitalist Democracies since World War II: Dealignment, Realignment, or Trendless Fluctuation?". Annual Review of Sociology. 21: 137–62. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.21.1.137.

- Marmot, Michael; The Status Syndrome: How Social Standing Affects Our Wellness and Longevity (2004)

- Marx, Karl & Engels, Frederick; The Communist Manifesto, (1848). (The key statement of class disharmonize equally the driver of historical change).

- Merriman, John M.; Consciousness and Class Feel in Nineteenth-Century Europe (Holmes & Meier Publishers, 1979)

- Ostrander, Susan A.; Women of the Upper Course (Temple Academy Press, 1984).

- Owensby, Brian P.; Intimate Ironies: Modernity and the Making of Middle-Course Lives in Brazil (Stanford University, 1999).

- Pakulski, January & Waters, Malcolm; The Decease of Class (Sage, 1996). (rejection of the relevance of course for mod societies)

- Payne, Geoff; The Social Mobility of Women: Across Male person Mobility Models (1990)

- Cruel, Mike; Grade Analysis and Social Transformation (London: Open up University Printing, 2000).

- Stahl, Garth; "Identity, Neoliberalism and Aspiration: Educating White Working-Class Boys" (London, Routledge, 2015).

- Sennett, Richard & Cobb, Jonathan; The Subconscious Injuries of Class, (Vintage, 1972) (classic study of the subjective experience of class).

- Siegelbaum, Lewis H. & Suny, Ronald; eds.; Making Workers Soviet: Power, Form, and Identity. (Cornell University Printing, 1994). Russia 1870–1940

- Wlkowitz, Daniel J.; Working with Class: Social Workers and the Politics of Eye-Class Identity (University of Northward Carolina Press, 1999).

- Weber, Max. "Course, Condition and Party", in eastward.chiliad. Gerth, Hans and C. Wright Mills, From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology, (Oxford University Press, 1958). (Weber's key argument of the multiple nature of stratification).

- Weinburg, Mark; "The Social Analysis of Iii Early 19th century French liberals: Say, Comte, and Dunoyer", Journal of Libertarian Studies, Vol. two, No. 1, pp. 45–63, (1978).

- Wood, Ellen Meiksins; The Retreat from Form: A New 'True' Socialism, (Schocken Books, 1986) (ISBN 0-8052-7280-i) and (Verso Classics, January 1999) reprint with new introduction (ISBN 1-85984-270-4).

- Wood, Ellen Meiksins; "Labor, the Country, and Form Struggle", Monthly Review, Vol. 49, No. three, (1997).

- Wouters, Cas.; "The Integration of Social Classes". Journal of Social History. Volume 29, Issue one, (1995). pp 107+. (on social manners)

- Wright, Erik Olin; The Debate on Classes (Verso, 1990). (neo-Marxist)

- Wright, Erik Olin; Class Counts: Comparative Studies in Class Analysis (Cambridge University Printing, 1997)

- Wright, Erik Olin ed. Approaches to Class Assay (2005). (scholarly articles)

- Zmroczek, Christine & Mahony, Pat (Eds.), Women and Social Class: International Feminist Perspectives. (London: UCL Printing 1999)

- The lower your social grade, the 'wiser' you are, suggests new written report. Scientific discipline. xx December 2017.

External links [edit]

-

Media related to Social class at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Social class at Wikimedia Commons - Domhoff, Yard. William, "The Class Domination Theory of Power", University of California, Santa Cruz

- Graphic: How Class Works. New York Times, 2005.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_class

Belum ada Komentar untuk "What are the 3 techniques used to rank people according to class? Describe and explain."

Posting Komentar